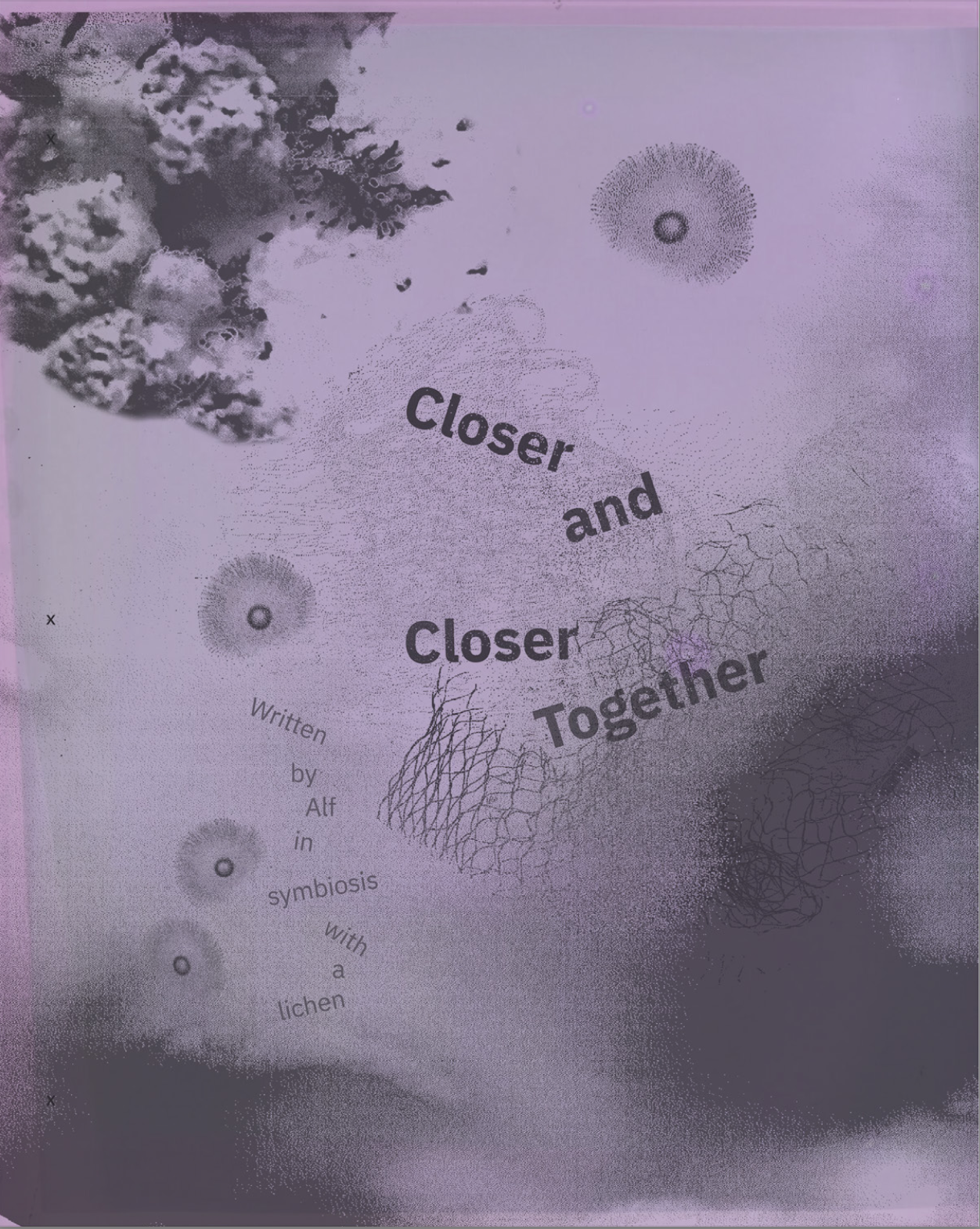

by Alf in symbiosis with a Lichen

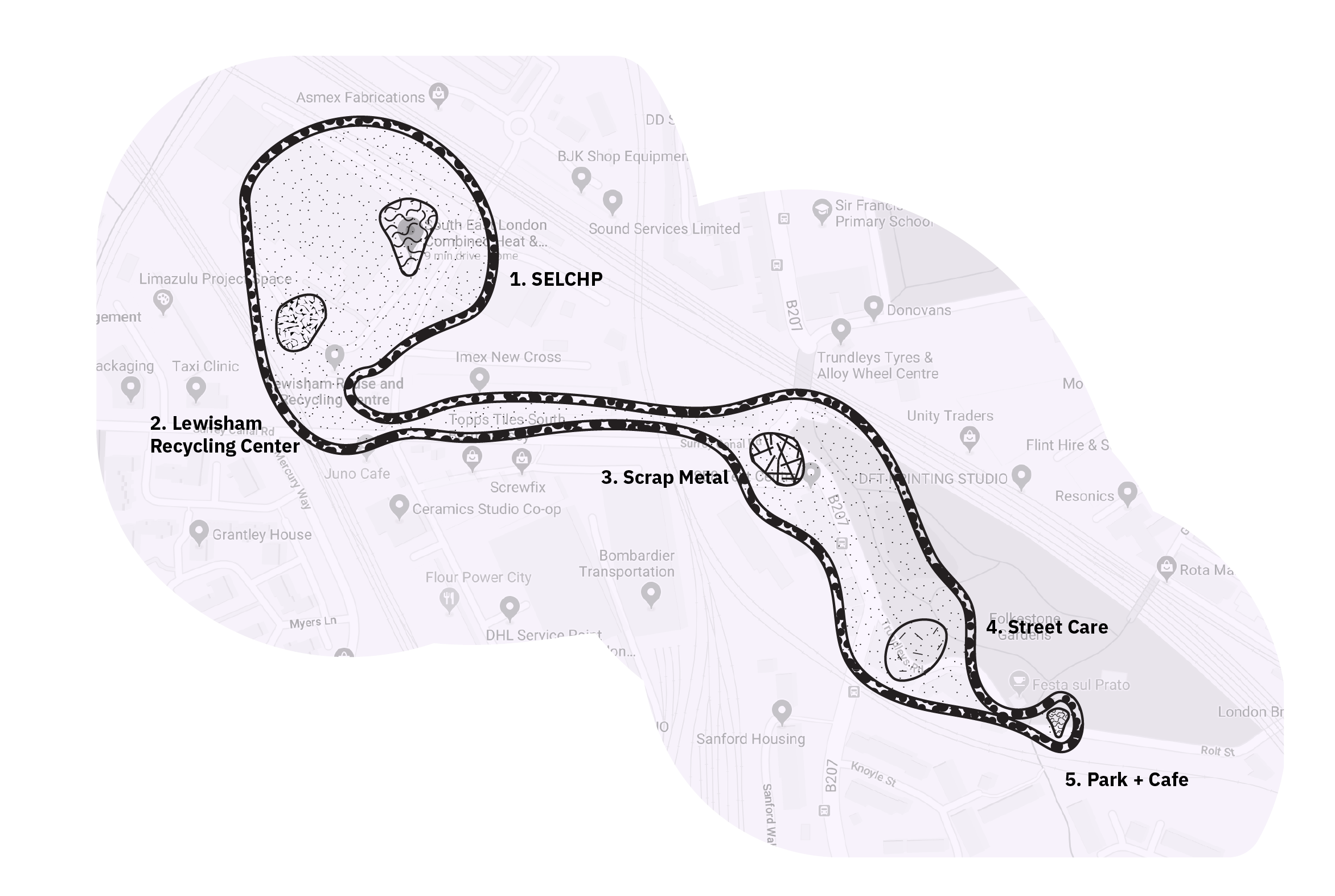

Closer and Closer Together consisted of a series of expeditions around the waste management infraestructures of SE London in order to explore the implications of becoming with a non-human being.

While trying to figure out where to locate my practice, I realised a lichen had been inadvertently growing on pebble I collected from the beach of Dungeness. I had that pebble on my desk for 9 months before realising I was developing a long lasting intimacy with a stranger; we were in symbiosis. We have found each other and we made kin: The lichen is with me; I’m with the lichen and we are cultivating response-ability for each other.

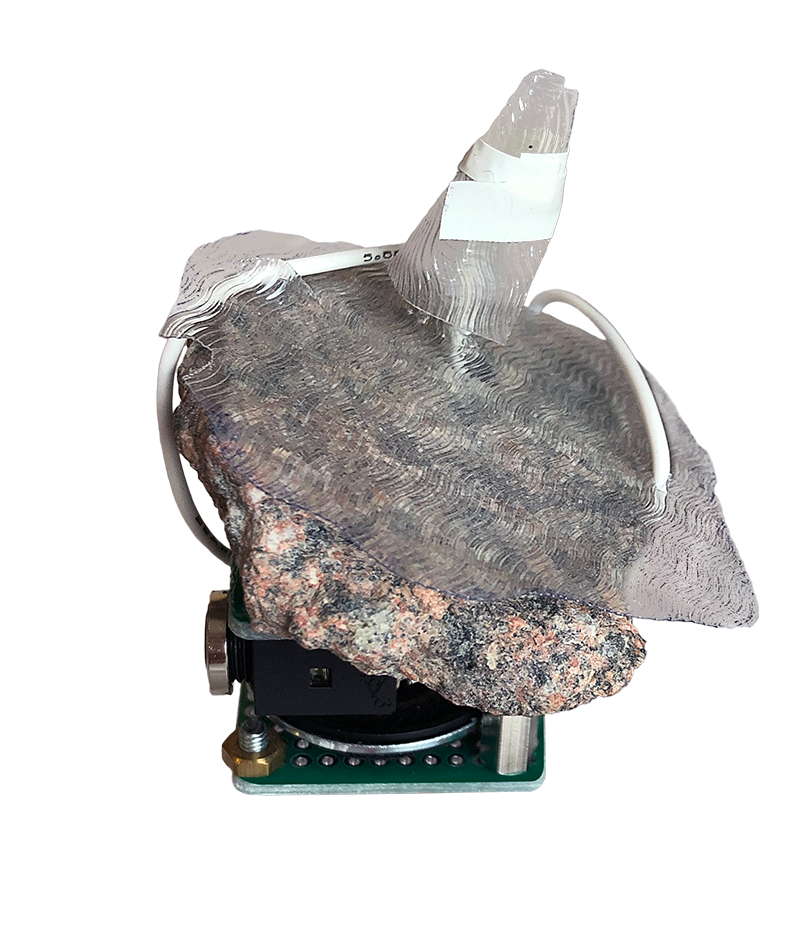

This unexpected encounter with life in a very sterile place (my desk) made me question how do we relate to life and position ourselves in relation to nature, also how to extend this kinship to those around me without exploiting or abusing my partner. In response I designed a set of devices that could let others replicate my encounter. The present genus of techno-lichens came to being along with a speculative cartography.

Read the full publication

Closer and Closer Together: Written by me in Symbiosis with a Lichen. Thesis publication for MA Design Expanded Practice Spaces and Participation at Goldsmiths, University of London.

Tambien en español :)

“A speculative fabulation exploring Design, Nature; a tale of becoming together for new ways of knowing and making times of ecological uncertainty.”

Techno-lichen #1 Personal waste brought to the expedition by Shyamli, pebble collected from Dungeness beach, light sensor, speaker and electronics

Techno-lichen #2 Personal waste brought to the expedition by Adolfo, pebble collected from Dungeness beach, light sensor, speaker and electronics

Techno-lichen #3 Personal waste brought to the expedition by Guoda, pebble collected from Dungeness beach, light sensor, speaker and electronics

Techno-lichen #4 Personal waste brought to the expedition by Rafel, pebble collected from Dungeness beach, light sensor, speaker and electronics

Closer and Closer Together: Written by me in Symbiosis with a Lichen. Thesis publication for MA Design Expanded Practice Spaces and Participation at Goldsmiths, University of London.

“A speculative fabulation exploring Design, Nature; a tale of becoming together for new ways of knowing and making times of ecological uncertainty.”